Widow's Weeds: Mourning Fashion in the Victorian Era

Posted October 1, 2025

Written by Sarah Matchette, Program Director

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

“I waited long, but all in vain,

To win my loved one back again.

Too late, alas! to weep and pray,

Death came; my loved one passed away.”

– from Regret, by Olivia Ward Bush-Banks (1869 – 1944)

___________________________________

Death and Dying in the 19th Century

The Victorian Era, which lasted from 1837 to 1901, was a time period with an intense focus on creating and maintaining rituals surrounding death and mourning. And it was no wonder, when life expectancy in the 19th Century was 40-45 years old at birth. Child mortality was also very high – around 20% of children died before the age of 5.

State Portrait of Queen Victoria in 1885, by Baron Heinrich Von Angeli Repro, Royal Collection Trust

This era was also set against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution, which led to many health problems for the population. The 18th and 19th Centuries saw a mass migration of people moving into cities- this led to overcrowding and horrible sanitary conditions. People who worked in factories were routinely exposed to dangerous chemicals and heavy machinery that could cause injury, such as the “Mad Hatters” who were poisoned by the mercuric nitrate they used to make their hats.

The Civil War was also a hugely impactful event here in the United States. Historians estimate that 750,000 people died during the conflict. Some soldiers made a full recovery while others succumbed to their wounds due to infections such as gangrene- ⅔ of the death count was caused by disease. Infection was a large driver of illness before the widespread acceptance of Germ Theory, making even hospitals unsafe.

“The Widow of Windsor”

Princess Alexandrina Victoria, born in 1819, would go on to become Queen of the United Kingdom in 1837 upon the death of her uncle, William IV. The monarch married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1840, and their partnership was said to be incredibly passionate. Over their 21 years of marriage, the couple had 9 children, and they often exchanged gifts and wrote of their affection for each other.

“How is it that I have deserved so much love, so much affection? I cannot get used to the reality of all that I see and hear, and have to believe that Heaven has sent me an angel whose brightness shall illumine my life.”

– Note from Prince Albert to Queen Victoria, October 1839, Royal Collection Trust

After Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria entered into a mourning period that lasted until her own death in 1901. Over 40 years, she wore her “widows weeds” (or black mourning wear,) she left his possessions untouched at their home at Windsor Castle, and she included Albert’s likeness in many family portraits. Victoria never remarried, and it was rumored that she attended seances in an attempt to communicate with her lost love. To this day, the prevailing image of Queen Victoria is of a monarch draped in black; English writer Kipling dubbed her, “the Widow of Windsor,” a fitting moniker for a woman who spent half of her life in mourning.

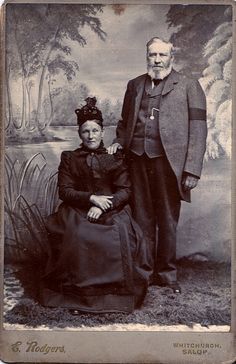

Mourning wear, Cabinet Card from 1880s-1890s, University of Michigan.

As the Queen of the United Kingdom and ruler of the British Empire, what Victoria said and did was witnessed by many, and she set the example for what was expected and even fashionable during the time period. The length and intensity of her mourning for Albert was what people looked to when they were mourning in their own lives, helping to set the stage for what historians refer to as the Victorian “cult of death.”

The Phases of Mourning

During the 19th Century, many Western countries followed specific stages of mourning, broken roughly into three categories:

-

- Deep, or High, Mourning

- Second Mourning

- Half Mourning

Deep Mourning was the longest and most intense of the stages. Second Mourning was a transitional stage, followed by Half Mourning, which was the short length of time before finishing the process. The length of each stage depended on a variety of variables, including:

Time Period:

Mourning rituals did vary depending on the decade. Sources as early as the 1860s discuss widows mourning for a year and a day, whereas sources from the 1890s discuss mourning a spouse for 2 years.

Relationship to the Deceased:

The length of time you mourned for a parent or spouse would be longer than for a cousin or friend.

Gender:

Mourning Dress, 1872-4, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Women whose spouses passed away would be in mourning anywhere from one to two years. Men whose spouses died would not be expected to mourn for longer than six months.

Geographic Location:

Mourning conventions in England or Europe could vary from the United States. For instance, in the U.S., it was customary to mourn the death of a public figure for thirty days.

Socio-economic status:

Beyond it being a societal expectation, the wealthy could adhere to strict mourning rituals and timelines because they had the time and money to devote to it. If you were poor, you would do the best you could with what you had- the same societal standards would have been present, but it could be harder to keep up with without the means.

Fashion Rules

Women had the most strict and elaborate rules for what to wear while in mourning. The goal was to be discreet and modest, and to show “proper” respect for the person who died.

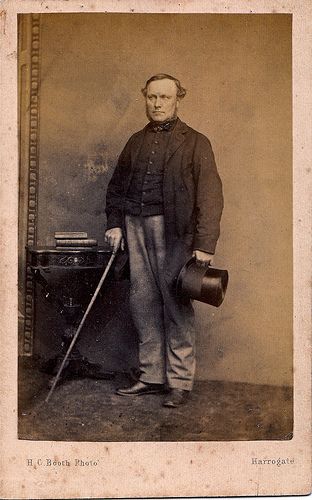

Mourning wear, Cabinet Card from 1880, Ann Longmore-Etheridge Collection.

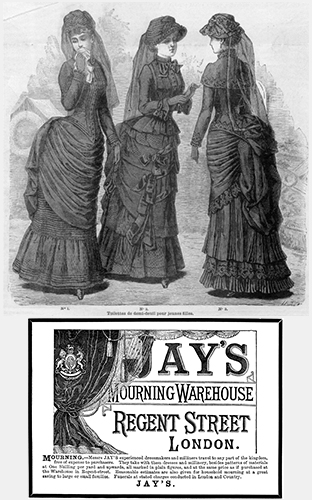

During High Mourning, women were expected to wear all black from head to toe- the fabric could not have any shine or color. Black crepe, a wool/silk textile that was dull and stiff, was the preferred material, but it was very expensive- many women would instead dye dresses or alter older styles. In public, it was also customary to wear a veil.

Once women moved into Second and Half Mourning, a bit of color and shine could slowly be introduced into the wardrobe. Gray, white, and lilac were often used in trim and detailing, and could become more dominant as mourning came to a close.

The fashion rules for men were much less restrictive. Generally, men would wear a black coat to signify they were in mourning, a sartorial choice that would not have deviated widely from what was worn normally. Another option was a black armband, which would have been helpful for anyone in uniform, such as those in the military or service industries. A male mourner could also add black fabric to their top hat, which was referred to as a weeper (the fabric hanging down echoed the veil worn by women in High Mourning).

Children were not expected to follow specific guidelines regarding mourning wear. Often, parents would dress their offspring in similar styles to themselves during this time.

Onyx Mourning Locket, 1871, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Mourning Essentials

Mourning wear became incredibly popular during this time period. Mourning bonnets, jewelry, gloves, umbrellas, and even stationary could be purchased from catalogs and at department stores. Jewelry made of jet and onyx was considered incredibly fashionable for mourning, and were pieces that could still be worn after mourning concluded.

There was a superstition that re-wearing mourning wear was unlucky, but it was unlikely that everyone was buying new clothing for each new death. There were places that rented mourning and funeral wear, including Jay’s Mourning Warehouse in London.

Mourning rituals extended to all aspects of everyday life, but the fashion of grief remains to be one of the most enduring and fascinating things to look back on from this time period.

Banner images: Exhibit gallery views from Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire, The Met, October 21, 2014–February 1, 2015.

Image carousel:

-

- Mary Todd Lincoln in mourning wear, Library of Congress

- Gentleman in mourning wear, University of Michigan

- Jet jewelry set from 1865-1870, British Museum

- Queen Victoria mourning dress, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Full mourning fashion, including jet jewelry, from “La Mode Illustrée, Journal de la Famille”, 1879

- Mourning dresses, from “La Mode Illustrée, Journal de la Famille”, 1883; Jay’s Mourning Wearhouse ad, circa 1890

Explore another Victorian Era mourning custom – hair art – by reading our blog article from October 2021, Hair We Are (PDF).

Learn more about Olivia Ward Bush-Banks, the poet we quoted at the beginning of this article, from Poets.org.

Resources

There are many wonderful resources out there on death and mourning during the 19th and early 20th centuries! These are a few that I used for this article, as well as for other programming here at The Square:

- “A is for Arsenic: An ABC of Victorian Death”, and “The Victorian Book of the Dead” by Chris Woodyard

- “Memory and Mourning: Death in the Gilded Age” by the Frick Pittsburgh Museum and Gardens

- William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan

- Fashion collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria & Albert Museum

- Archives of the Royal Collection Trust

______________________

Thank you for reading our history blog!

Archive

-

2025

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (2)

-

April (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-