Childcare and World War II

Posted September 1, 2025

Written by Heather Roberts, Research Historian

For a printable, PDF version of this article, please click here.

“The impact of war which resulted in unsettled family and community conditions brought about an unprecedented demand for child welfare services.”

– Annual Report of the Arizona State Board of Social Security & Welfare, 1943-44

Did you know…

In our search for the individuals who lodged or boarded at Rosson House during the 20th century, there are 5 people we know lived there, but whose names and further information remain a mystery. Two things make discovering who they are or were more challenging: first, these 5 people were children, and second, that they lived at Rosson House alone, without their parents.

Why would those things make it harder to find them?

Because children are not listed in many of the public records we regularly use to look for former residents of the Square, like city directories, phone books, voter registrations, and draft registration cards. If their parents/guardians had lived in Rosson House with them, then we might run across the adults’ information, and then be able to connect the kids to the home through them.

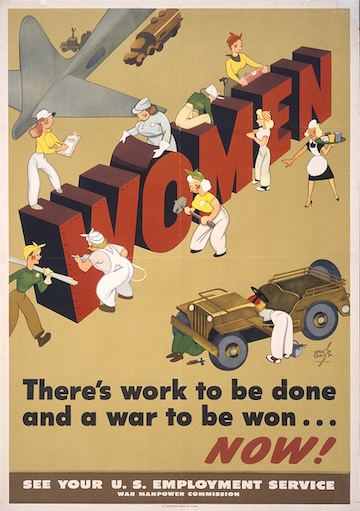

A poster urging American women to join the war workforce, 1944. From the Library of Congress.

The bigger question of why a group of children would be living at Rosson House, or anywhere else for that matter, without their parents or guardians has a simple answer – the war.

The Changing World War II Workforce

In 1940, just over 13 million women were a part of our nation’s workforce, making up a quarter of all workers, primarily in jobs that were traditionally seen as “women’s work,” such as teaching, nursing, and domestic labor. When the US entered World War II, however, millions of men were drafted to fight, leaving significant gaps in the workforce. At first, there was pushback to women taking up jobs to help the war effort. This was in part because the idea of children being cared for outside the home and away from their mothers was seen in a negative light. But the high demand for increased production of war materials meant that women were actively encouraged to take these jobs. Eventually, another 6 million women would join the workforce during the war years, in jobs – like that of the iconic “Rosie the Riveter” – that had traditionally been unavailable to them. As these women entered the labor market, providing adequate and consistent childcare for workers became critical to the war effort.

As the war entered its second full year for the US with no end in sight, and with authorization from the Defense Housing and Community Facilities and Services Act of 1940 (also known as the Latham Act), Congress earmarked $20 million to establish “war nurseries” across the nation, including here in Arizona. The childcare centers standardized care – providing hot meal meals (with food being rationed during the war, this was a big deal), and also providing educational learning and areas for both rest and play. They were funded all or in part by the federal government, along with state funds and admission fees from around 50 cents to a dollar per day (Note: This would be $9.34 to $18.67 today, adjusting for inflation). Childcare centers were initially established for children younger than school age, but many care facilities were added in elementary schools as need for after school care was realized.

Food like sugar, coffee, cooking fats like butter and lard, meat, cheese, processed foods, and canned goods were all rationed during World War II. Families were issued ration books – one for each person – and a limited number of stamps that had to be used when purchasing rationed foods. Many families supplemented their diets by planting Victory Gardens.

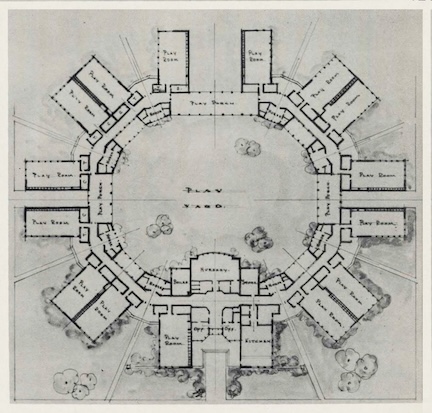

Part of a sketch of the planned Kaiser childcare facilities from the Bo’s’n’s Whistle, July 1, 1943. Image from the Library of Congress

The Kaiser shipyards in California, Oregon, and Washington took the initiative to invest in what they called Childcare Development Centers near their facilities that were convenient to their workers in both location and available hours, leading to an increase in production and a decrease in work absences. According to the July 1, 1943 edition of the Bo’s’n’s Whistle, an employee newsletter for the shipyards, each center would cost approximately $250,000 to build (equaling over $4.6 million each in today’s value), and the daily fee was $1.00 per child. They were staffed by education and childcare professionals, had indoor and outdoor play areas, and nurseries for infants, They also provided a bus service for kids and parents, medical care for the children, and a food service for an affordable fee, where parents could pick up a pre-cooked and packaged meal for the whole family when they picked up their child at their end of their shift.

In theory, Kaiser childcare centers were open to the children of all of their workers, but overt racism forced most Black families to have to personally arrange care for their children elsewhere.

Childcare in Arizona During WWII

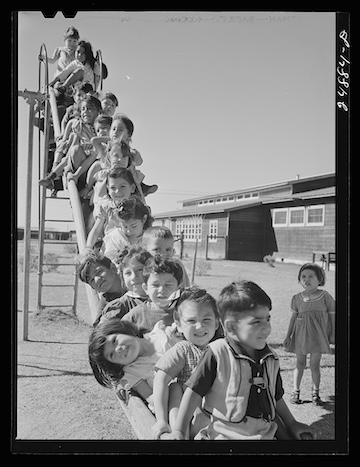

Children at a childcare center playground, Robstown camp, TX, 1942. From the Library of Congress.

During the war, Phoenix was a center for defense industries, and workers flocked to the area to fill available jobs at companies like Goodyear, ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America), and AiResearch. With the surge in workers came an equal increase in the need for childcare. In September 1942, the Works Projects Administration (WPA) opened a childcare center at the Social Service Center at 7th and Adams (across the street from the Square’s Silva House), and others were opened at the University Park playground at 10th and Van Buren, and the Phillis Wheatley Community Center at 14th and Jefferson, which was specifically intended for African American children, as Arizona schools were still segregated at this time. A center already existed at the WPA migratory camp at Agua Fria (approximately 17 miles west of Phoenix), dating to the years of the Great Depression. The Phoenix childcare centers provided lunch and a snack, periods of play and resting, crafts, indoor games, storytelling, and trips to the park and/or library. Childcare centers were also opened in other Arizona towns, like Globe and Douglas, and funds to build centers were allocated to the Wilson, Avondale, and Tempe school districts as well as to Luke Air Force Base.

But just providing reliable childcare while parents and guardians were working wasn’t the only issue for local communities during the war.

On September 19, 1943, an article in the Arizona Republic newspaper announced that the Arizona State Department of Social Security & Welfare was working with the Social Service Center and four community groups – an African American Parent-Teacher Association, the Catholic Social Service, the Jewish Welfare Council, and Friendly House – in what they called the “United Home-Finding Campaign”. Its purpose was to find foster homes for children whose parents or guardians were unable to care for them because of the war, The state would provide a monthly food allowance for the children, arrange for food rationing and clothing (which was also rationed), coordinate medical care, and pay a boarding rate* to the foster family. The coalition found 80 foster homes within the first five days of the campaign. (*The 1945-46 report of the Arizona State Board of Social Security & Welfare, stated that the predominant boarding rate was $30-$35 per child, per month.)

A Possible Rosson House Connection

With the severe lack of available housing in many areas during World War II, including in Phoenix, people were urged to open their homes to those who worked in defense industries in a “Share Your Home” campaign – particularly those workers who had children. Sharing their home was the norm for the Gammel family while they lived at the Square, and they housed at least 15 lodgers at Rosson House during the war years. According to an interview with Georgia (Gammel) Valiere, 5 of those people were boys who attended St. Mary’s school, located just down the street from their home. Unfortunately, this brief mention of the boys from Georgia’s interview is all the information we have about them.

Rosson House from the Historic American Buildings Survey, circa 1940.

To start, we contacted St. Mary’s, and then the archives of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix, to see if they had anything in their records about helping families find housing for their children during the war. But after a thorough investigation, neither had the information we’re looking for.

It’s possible, however, that the kids were placed with the Gammel family through the state led United Home-Finding Campaign mentioned earlier. Two things make us think that is likely: First, one of the organizations listed is the Catholic Social Service, a local charity organization established in the 1930s. It seems reasonable to think that organization would have recruited foster families from those who, like the Gammels, already attended local Catholic churches in their search for foster homes. Secondly, the close proximity of Rosson House to the Social Service Center, which was the campaign headquarters for the home-finding project, may have helped target the house as a potential foster home, particularly if the employees there already knew the Gammels took in lodgers. If the boys were placed through this campaign, the state might have information about the Gammels the students who were placed with them. We’ve contacted the Arizona State Department of Social Security & Welfare, now the Arizona Department of Economic Security, to see if they may have any archived records connected to the 1943 campaign. Their Public Records Office is currently working to see if the information exists, and if so, if they can share it with us. Keep your fingers crossed!

Post-War Childcare

It’s estimated that up to 600,000 children were cared for in federally funded childcare centers during the war. But when the war ended, these facilities closed. Whether they wanted to or not, the vast majority of women who joined the workforce, or had moved from trades considered to be “women’s work” to those traditionally dominated by men, left those positions and went back to the home or to their pre-war jobs. The government stopped funding childcare, as did the industries who had so relied upon it for their workers during the war. Women now make up close to half our total workforce and are still predominantly the primary caretakers of children within American families. Because of this, the need for reliable and affordable childcare is still as prevalent today as it was over 80 years ago, if not more so. However, national efforts to fund a universal childcare program similar to that enjoyed by families during World War II have not succeeded.

The Mochida children as their family prepares for incarceration, Hayward, CA, May 8, 1942. From the Library of Congress.

Learn how the children from the “Children’s Village” of California’s Manzanar concentration camp – a facility used to imprison Japanese American infants and children during World War II – made it through the war without their parents or guardians.

Explore the world-changing events that led up to World War II in our blog articles, Arizona at War: World War I, and Arizona & the Great Depression.

Banner Photo: Children at a World War II childcare center in Oakland, CA, April 1943. From the Library of Congress.

-

Reference List

- 1940 Census of Population: The Labor Force (Sample Statistics). Bureau of the Census, 1943.

- Arizona State Department of Social Security and Welfare. “1943-1944, Arizona Annual Report of the State Board of Social Security and Welfare and the Commissioner of the State Department of Social Security and Welfare.” Arizona Memory Project, 1944, azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/325935. Accessed 24 July 2025.

- —. “1945-1946, Arizona Annual Report of the State Board of Social Security and Welfare and the Commissioner of the State Department of Social Security and Welfare.” Arizona Memory Project, 1946, azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/325930. Accessed 26 July 2025.

- Curd, Mary Bryan. “Child Service Centers, Swan Island Shipyards.” Oregon History Project, 2015, www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/child-service-centers-swan-island-shipyards/. Accessed 10 Aug. 2025.

- Dratch, Howard. “The Politics of Child Care in the 1940s.” Science & Society, vol. 38, no. 2, 1974, pp. 167–204. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40401779, https://doi.org/10.2307/40401779. Accessed 15 Aug. 2025.

- Ertman, Thalia. “The Lanham Act and Universal Childcare during World War II.” Friends of the National WWII Memorial, 27 June 2019, www.wwiimemorialfriends.org/blog/the-lanham-act-and-universal-childcare-during-world-war-ii. Accessed 12 Aug. 2025.

- Harper, Marilyn M., et al. World War II and the American Homefront: A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study. The National Historic Landmarks Program, Oct. 2007.

- Little, Becky. “The US Funded Universal Childcare during World War II, Then Stopped.” History, 12 May 2021, www.history.com/articles/universal-childcare-world-war-ii. Accessed 2 Aug. 2025.

- Melton, Brad, and Dean Smith. Arizona Goes to War : The Home Front and the Front Lines during World War II. Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 2003.

- Michel, Sonya. Children’s Interests/Mothers’ Rights : The Shaping of America’s Child Care Policy. New Haven ; London, Yale University Press, 2000.

- Mintz, S., and S. McNeil. “Children and the Great Depression.” Digital History, 2018, www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/children_depression/depression_children_menu.cfm. Accessed 7 July 2025.

- Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation. “Nurseries for the Three Yards.” The Bo’s’n’s Whistle, vol. 3, no. 13, 1 July 1943, p. 3, digitalcollections.ohs.org/the-bosns-whistle-volume-03-number-13. Accessed 10 June 2025.

- Rose, Evan K. “The Rise and Fall of Female Labor Force Participation during World War II in the United States.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 78, no. 3, Sept. 2018, pp. 673–711, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-economic-history/article/rise-and-fall-of-female-labor-force-participation-during-world-war-ii-in-the-united-states/66C7D7FD7F6424DF40625E913DDC788F, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050718000323. Accessed 10 Aug. 2025.

- Stroman, Sarah. Food, Comfort, and Care: Women Workers at Kaiser’s WWII Child Service Centers. The Oregon Historical Society, 22 Mar. 2022, www.ohs.org/blog/women-wwii-childcare-workers.cfm. Accessed 20 July 2025.

- The Arizona Republic. “Eighty Homes Answer Drive.” Newspapers.com, 25 Sept. 1943, www.newspapers.com/image/117129440/. Accessed 12 July 2025.

- The Arizona Republic. “Foster-Homes Are Sought for Young Babies, Children.” Newspapers.com, 19 Sept. 1943, www.newspapers.com/image/117066437/. Accessed 12 July 2025.

- The Arizona Republic. “Share-Home Drive Opens.” Newspapers.com, 5 Oct. 1943, www.newspapers.com/image/117143647/. Accessed 8 Aug. 2025.

- The National WWII Museum. Rationing. 2024, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/rationing-during-wwii. Accessed 26 June 2025.

- Wagner, Ella. “Childcare on the World War II Home Front (U.S. National Park Service).” National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park, 11 Sept. 2023, www.nps.gov/articles/000/childcare-on-the-world-war-ii-home-front.htm. Accessed 10 July 2025.

Archive

-

2025

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (2)

-

April (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-